Christopher Thompson and Fiona Ratkoff, “'A Third Sex'

Bourgeois Women and the Bicycle in Fin de Siècle France” (2)Gender, Bicyles, and National Security

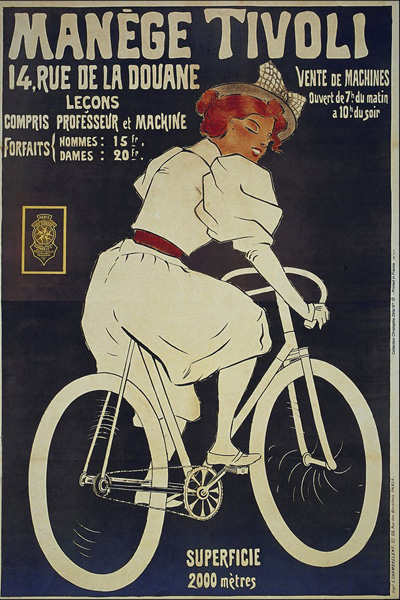

The New Woman in France at the End of the 19th Century

The disquiet of the French at the end of the century concerning the emancipation of women was not entirely the product of obsessions and irrational insecurities. During the last decades of the 19th century French women, above all those of the middle classes, acquired a new status. The measures which ameliorated their educational possibilities, their professional options, and their rights opened the doors for them to domains that had formerly been exclusively masculine. . . .

The improvement of the status of women was continued throughout the Belle Epoque by  the activities and the great notoriety of feminists, who created newspapers, held congresses covered by the press, and founded organizations of women, often affiliated to international organizations. At the end of the 19th century the woman’s question had become an important subject of French cultural production and political discourse, widely dealt with in the press, literature, and plays of the era. For many of the French this trend was personified by female cyclists. Feminists, such as Maria Pognon, who presided over the feminist congress of 1896, welcomed the equalizing bicycle that would liberate the woman. But what Maria Pognon celebrated in the bicycle, others found profoundly troubling. . . . The specter of a new generation of independent and infertile women going across the countryside on bicycles disturbed many of their contemporaries who believed that the emancipation of women not only represented an attack on the authority of the father of the family, but also through its demographic consequences, threatened the very security of the nation.

the activities and the great notoriety of feminists, who created newspapers, held congresses covered by the press, and founded organizations of women, often affiliated to international organizations. At the end of the 19th century the woman’s question had become an important subject of French cultural production and political discourse, widely dealt with in the press, literature, and plays of the era. For many of the French this trend was personified by female cyclists. Feminists, such as Maria Pognon, who presided over the feminist congress of 1896, welcomed the equalizing bicycle that would liberate the woman. But what Maria Pognon celebrated in the bicycle, others found profoundly troubling. . . . The specter of a new generation of independent and infertile women going across the countryside on bicycles disturbed many of their contemporaries who believed that the emancipation of women not only represented an attack on the authority of the father of the family, but also through its demographic consequences, threatened the very security of the nation.

National Security, Maternity, and the Female Cyclist

The demographic figures for France in the last decades of the 19th century confirm the extent to which French anxieties were justified. Between 1870 and 1914 the French birth rate fell 27.4%. There were more deaths than births between 1890 and 1895, in 1900, 1907 and 1911. Between 1872 and 1911 the French population grew by 10% as that of Germany went beyond 58% (an increase of 600,000 per year). . . .

These alarming numbers encouraged an increasingly pronatalist politics [i.e. political initiatives intended to raise the birth rate], particularly after 1890, that was expressed in the creation of pronatalist organizations and of legislation favoring maternity. During the last decade of the 19th century, diverse observers made feminism responsible for the fall in the birth rate. The fear of seeing young women postponing, or worse rejecting maternity rapidly took on an obsessional dimension. The protection of the traditional family (and at its heart the procreative role of the mother) was a question of national security and the guarantee of a powerful army in the future. According to the maxim of the younger Alexandre Dumas in 1887, “maternity is the patriotism of women. . . .

Hygenists promised an increase in French natality if women had more exercise in a reasonable and judicious manner, but female sports violated the idea that women were “the angels of the home,” hypersensitive, sweet, maternal, fragile, and delicate. . . .

The medical debates about cycling in this era did not limit themselves to the impact of the sport on women. In fact, the French doctors were deeply divided as to the effects of this new sport on the human body in general. The popularization of the bicycle coincided with the “scientific” diagnosis of the degeneration of the French at the end of the 19th century, which was in great part analyzed as a physical problem which could be regulated by physical education and sports. The French turned to their doctors to combat this national scourge, and the doctors, for their part, undertook the study of the physiological, neurological, and psychological impact of cycling, one of the most popular sports of the era. . . .